The White Rose of Stalingrad

Review

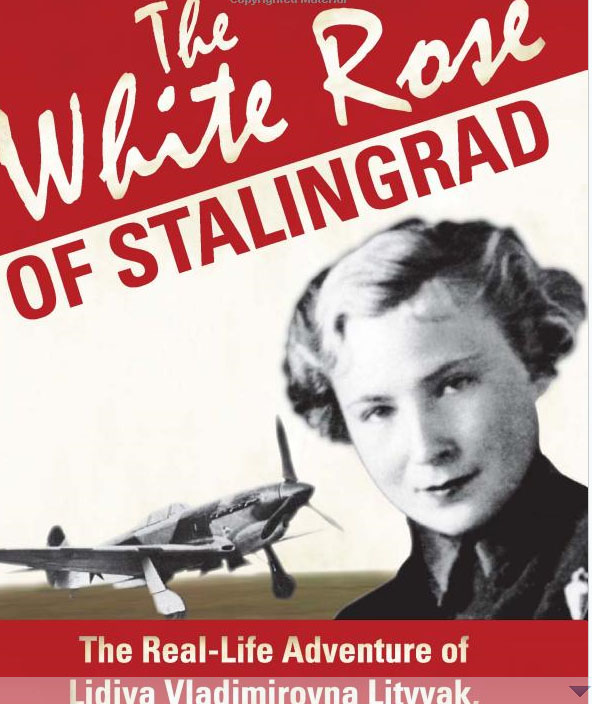

The White Rose of Stalingrad: The Real-life Adventure of Lidiya Vladimirovna Litvyak, the Highest scoring Female Air Ace of All Time, Bill Yenne, Osprey Publishing, 2013, 319p, ISBN 9781849088107. £20-00.

The title of this extraordinary book does not fully convey the full breadth of what this book reveals and explores.

It does fully recount the air-force career of an extremely brave and exceptional fighter pilot, especially unusual because of her gender. She disappeared in combat over the Ukraine at the age of twenty-one, having been credited with at least twelve ‘hits' and having been involved in the desperate Russian campaign to stem the Nazi advance towards, and beyond, Stalingrad. Her prominence arises in part from the recruitment of three all-women airforce regiments which then enabled women fliers to demonstrate their prowess, although some of Lidiya Litvyak's greatest achievements were recorded serving as ‘wing' support in regular Russian airforce squadrons. Her title was earned from her tendency to decorate her cockpit with wildflowers and to paint a white lily on the fuselage - not quite the ‘white rose' of her title!

However Bill Yenne offers us very much more than the detail of a Lidiya's flying career. In setting the scene for her career, he introduces us to the internal political, social and economic situation of Russia under Lenin and, more particularly, under Stalin. He provides a very critical commentary of the economic strategies of the two Russian leaders, with his most severe observations being reserved for Stalin and the fact that his heroic Five Year Plan strategy clearly was significantly less successful than how the propaganda depicted it. He then explains how this lack of success was inter-related to Stalin's paranoia which led to a huge programme of purges in the late 1930s, with Stalin's suspicions encompassing vast numbers of loyal party members.

What is so remarkable, however, is that someone like Lidiya Litvyak could lose her father in the later stages of these purges and yet remain loyal to Stalin and Russia. Bill Yenne explains this in the wider context that many Russians traditionally had expected Russia to have a ‘father' figure, and such a person was to be held in absolute awe, along with another belief in the Mother Russia' [or Godina]. Despite her family's distress at what had happened to her father, Lidiya shared this traditional over-riding belief, in effect, in the absolute importance of these ‘father' and mother' figures for Russia, in other words her innate nationalism, which enabled her to separate her personal distress from her determination to serve Russia. In providing this analysis Bill Yenne has helped me to understand better how Russian nationalism survived Stalin's excesses.