A History of Birmingham's Municipal Parks 1844-1974

Review

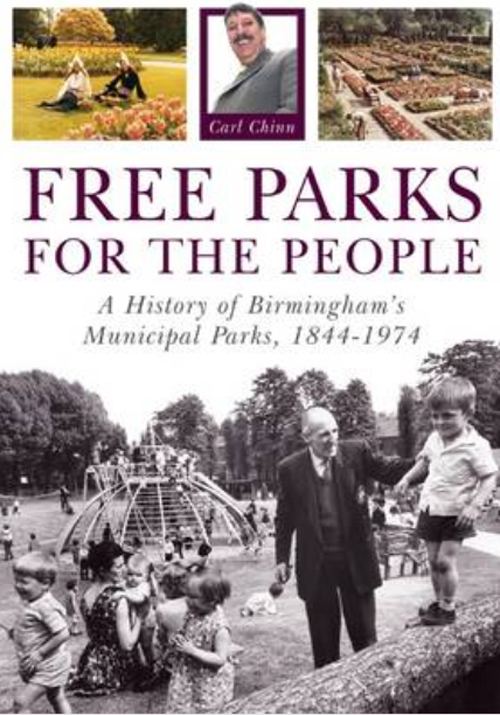

Free Parks for the People: A History of Birmingham's Municipal Parks 1844-1974, Carl Chinn, Brewin Books, 2012, 160p, paperback. ISBN 978-1-85858-495-9. £14-95.

Even people who have strong affinity with Birmingham will find what Carl Chinn reveals in his ‘Free Parks for the People' to be an extraordinary story. That Birmingham is blessed with such a large extent of parkland and recreation grounds finds its origins in the mid-19th Century in the minds of people of various kinds who sought to provide open spaces for leisure and exercise for the ever-burgeoning metropolitan population. Philanthropic individuals, thoughtful and progressive clergy and businessmen together with working class people, who had higher aspirations for their collective lifestyle, combined to bring the first parks into public use, at various stages with some obstruction from some local politicians who were concerned about public expenditure levels. In some senses it all seems so familiar.

The earliest parkland provided was just outside the Birmingham local government boundaries, including Adderley Park [1856], Calthorpe Park [1857] and Aston Park [1858]. The last of these was opened by Queen Victoria, who then maintained an interest in what was happening there, with its financial difficulties. These latter led to fund-raising endeavours, during one of which a female tight-rope walker fell to her death, thus prompting the Queen to intervene, and this intervention ultimately led to the Aston Park funding crisis being resolved.

One of the themes which Carl Chinn rightly emphasises is the extraordinary alliance between socially-concerned Tories, philanthropists, progressive clergy, radical politicians, thoughtful businessmen and skilled workers which led to the formation of the Public Recreation Society in 1855; and various combinations of this alliance were to be seen at work at various instances in the years that followed. Quite evidently in the provision of public parks and recreation grounds in the mid-19th Century, public opinion was well ahead of local government decision-making.

Anyone who has enjoyed public parks and recreation grounds will find this book a useful template against which to compare the emerging Birmingham provision with their own experience. Young people enjoy parks and open spaces, as I did, without thinking about the planning and political manoeuvring which led to this provision. This is very helpful in compensating for our youthful ignorance and in creating a context for our various experiences.