Women and the Great Hunger

Book review

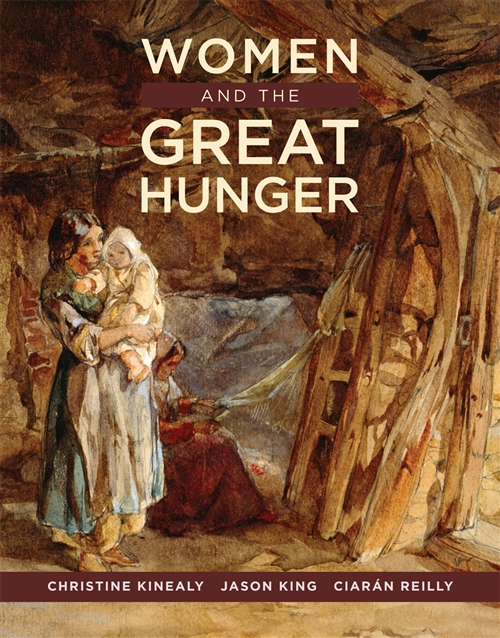

Women and the Great Hunger, Christine Kinealy, Jason King and Ciaran Reilly, Cork University Press, 2017, paperback, 236 pp., £21.95, ISBN 97809909454

The seventeen editors and authors contributing to this groundbreaking study include some of the leading researchers in Irish studies, offering new scholarship, methodologies and perspectives on this immense tragedy and its multiple legacies. They make it clear at the outset that ‘even considering recent advances in the development of women’s studies as a discipline, women remain underrepresented in the history and historiography of the Great Hunger’. Little attention, they insist, has been given to ‘the diverse roles played by women as landowners, relief-givers, philanthropists, proselytisers and providers for the family’.

Drawing on folklore and popular culture as well as more traditional sources, this publication ‘examines the diverse and still largely unexplored role of women during the Great Hunger, shedding light on how women experienced and shaped the tragedy that unfolded in Ireland between 1845 and 1852’.

The first of a dozen appended images is a photograph of Cecil Woodham-Smith receiving an Honorary Doctorate. Woodham-Smith's classic account of ‘The Great Hunger’ introduced me as a sixth former to this appalling tragedy. The first chapter, by editor Christine Kinealy, is entitled ‘"Never Call Me a Novelist"’: Cecil Woodham-Smith and The Great Hunger’, and accurately asserts that this stimulating and poignant book ‘retains a freshness and energy that belies its age’. Whilst she remains critical of the multi-authored official history The Great Famine, Studies in Irish History, she cites one of the editors, Dudley Edwards, who comparing the volume with Woodham Smith’s Penguin paperback predicted privately that the volume would have the feel of ‘dehydrated history’ in contrast to Woodham Smith’s classic which possessed the ‘ability to be on fire’.

Other chapters, too many to discuss individually, include Maureen Murphy’s brief but informative study of the contemporary American schoolteacher, reformer and philanthropist who visited Ireland in 1844 and 1845 and wrote about her experiences in 1847, particularly in her encounters with Irish schoolchildren. They also include Ciaran Reilly’s study of the female petition during the Great Hunger, Cara Delay’s evaluation of women, priests and authority during the famine era and Daphne Wolf’s exploration of clothing and the Great Hunger, several articles on the impact of the famine on Irish culture and emigration to America, Australia and Canada.

Such a wide-ranging collection of studies from such a distinguished range of contributors make this book an essential starting point for further research into this tragic episode.