Teaching History 199: Out now

The HA's journal for secondary history teachers

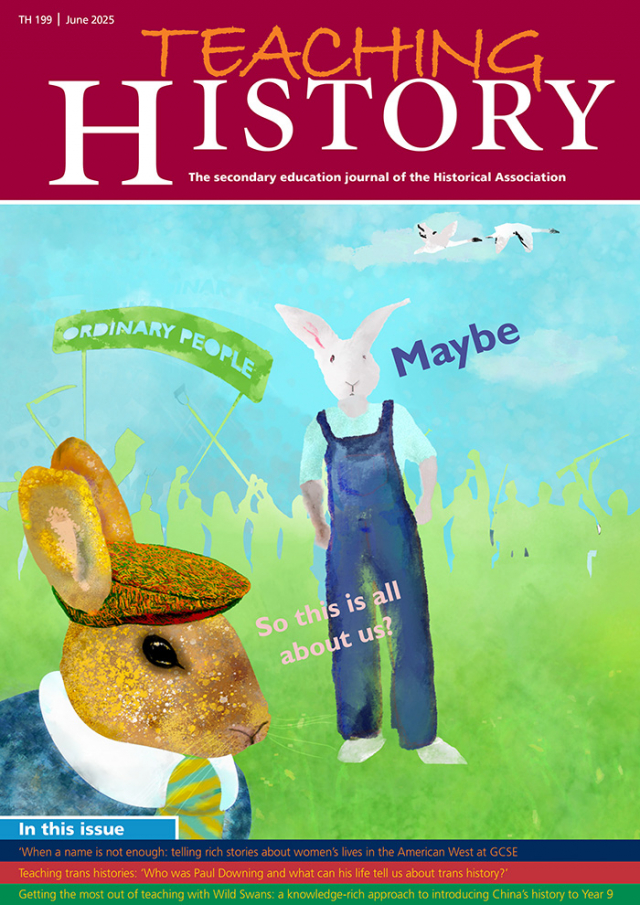

Editorial: Ordinary People

Read Teaching History 199: Ordinary People

We editors always enjoy kicking around ideas for the theme of each edition of Teaching History. It sometimes surprises readers to learn that we don’t come up with a title, and then commission articles. Rather, we immerse ourselves in the scores of proposals that come our way. We then group and classify them in a giant ‘card sort’, until themes emerge.

Even then, we don’t finalise the title; we wait until quite late in the editorial process for that edition. We then continue the fun by debating options until some apposite and eye-catching wording emerges. We wait until we’re confident that the title really does reflect a common theme in what our authors have actually written.

This edition’s theme, ‘Ordinary People’, was possibly both the easiest and the hardest title we have had to find. It was easy because, quite early in the giant card-sort, the words ‘ordinary people’ came to mind. In the proposals we were reading, we saw teachers being determinedly creative, not only in diversifying the range of people whose stories they teach, but also in showing the agency and complexity of those people – people who could not control official, subsequent narratives.

A decision on the title was hard, however, because ‘Ordinary People’ sparked nagging doubts. We pondered ‘Ordinary Lives’. No, that was worse. ‘Ordinary’ has connotations of being unremarkable, unworthy of note. To be ‘ordinary’ is to be like numerous others, with nothing to distinguish them. This left us uncomfortable. The individuals and peoples whose histories these teachers were uncovering were indeed remarkable. Moreover, because of their agency in shaping their own or subsequent worlds, these ‘ordinary’ lives not only reveal neglected layers of social and cultural history, but also allow new versions of more traditional, political narratives – written about (and by) the powerful – to be told.

So in plumping for ‘Ordinary People’, we do so with some irony. These are people deemed ‘ordinary’ by tradition, perhaps by virtue of their facelessness in the historical record, perhaps through holding life experiences in common with thousands of others, but the study of any one of them reveals a remarkable life – and often a life that, knowingly or not, played its part in making the world change.

As ever, we noticed our authors extending and enriching existing teachers’ work. Nicole Ridley was influenced by Susannah Boyd (TH 175). In her article about women in the American West, Ridley writes:

I thought I was doing a good thing by including women’s names in a new scheme of work. Boyd’s article, however, issues a challenge to change the way we think about women and their agency in the past. Rather than just adding a few women’s names to a traditional narrative, we can use gender as a lens to re-evaluate the narrative: the characters, the plot, where to begin the story and where to end it.

And so, for Ridley, the study of women became a way of not just altering who appears in the story, but of changing the fundamental shape of the story itself.

Freya George also engaged her students with a woman’s voice – in this case a famous one, that of Jung Chang, author of Wild Swans. Problematising the word ‘wild’, George helped her students to see how the story of Chang, her mother and her grandmother, was not only ‘wild’ in its challenge to the official Chinese narratives, but also invited a fresh or ‘wild’ reading of Chinese history, through the experiences of three generations of women.

All our authors have also sought to engage students with processes which have made so-called ‘ordinary people’ appear voiceless – in other words, to teach about disciplinary matters of evidence, interpretation or significance. Recently, Rachel Foster (TH 197) suggested that students’ reflection on significance is necessarily a reflection on silence. Drawing on the Haitian academic, Trouillot, she argued for a rebranding of the well-known curriculum staple of significance as ‘significance and silence’.1

These silences enter the historical record during different stages in the production of historical knowledge. Sometimes, silence is deliberate, sometimes it arises from accidents in the survival of sources, sometimes it emerges from historians’ interests, ideology, context or methods, and sometimes (whatever its cause) it is ossified by tradition or popular memory. It was by studying local ‘ordinary’ people in fourteenth-century St Albans that Steve Clarke, John Mitchell and David Ingledew showed students how to disrupt established narratives of the 1381 Revolt. They did this by drawing on rich resources of local heritage, giving students a vibrant encounter with specific local people, places and events.

Peter Anderson and Alex Clifford elaborate on the value of sources in teaching about working-class volunteers who fought in the Spanish Civil War. Students were stretched in their evidential reasoning by having to interpret raw and emotional testimonies – a striking contrast with sources written in ‘the guarded language of the ruling classes’, so familiar from GCSE examinations. Lucy Capes, Remi Graves and Onni Gust also had students engage with sources, but they chose to foster a more visceral response. Adding in a cross-disciplinary dimension, they explore the power of poetry to engage with the fragments and traces of those, such as Paul Downing, who did not conform to the gender norms of their time.

Capes, Graves and Gust, in their co-authoring as teacher, historian and poet, also embody an increasingly common sub-theme of many editions of Teaching History: those empowering collaborations in which history teachers increasingly engage, with academic historians, heritage professionals, archivists and artists.

References

1. Trouillot, M-R. (2015) Silencing the Past: power and the production of history, 2nd Revised Edition, Boston, Mass.: Beacon Press, pp. 22–23.