American Dime Novels 1860-1915

GCSE Topic Pack

|

This resource is free to everyone. For access to a wealth of other online resources from podcasts to articles and publications, plus support and advice though our “How To”, examination and transition to university guides and careers resources, join the Historical Association today |

Dime novels | Dime novel craze | Publishers | Authors | Audience | Lasting influence | Further reading

Dime novels

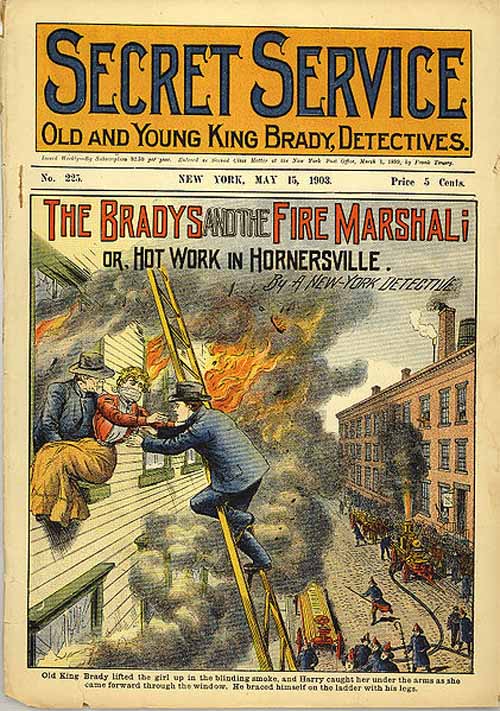

The first dime novels were initially published around the start of the American Civil War. These sensational stories were full of romance and adventure and became wildly popular in both the United States and in England, where they were known as "penny dreadfuls." Named for their cheap prices, dime novels were distributed in numerical series at newsstands and dry goods stores for a dime or a nickel a piece. The books were simple in appearance, bound in cheap paper with a brightly illustrated cover. They were lightweight at only about 100 pages long, easy to carry, and easy to pass around.

Because of the cheap price of the dime novels, publishers geared the books toward the uneducated lower class, producing stories with simple, formulaic plots that opened "new worlds" to their readers. Storylines were straight forward and told in physical language that brought to mind concrete pictures and people for the readers. There were no mind games or psychoanalysis in the novels, only simple story telling. For the less avid reader, story papers were published with abridged versions of dime novel-like stories. These were shorter and brightly illustrated. Most often they were about eight pages in length and serialized weekly in magazines or booklets.

The first of these stories were about the American Indians, but when Indians were placed on reservations, the public's fascination with them began to fade. Consequently, the novels morphed into stories of cowboys in the Wild West, outlaws and bandits, and train robbers. Detective mysteries and working-girl narratives followed later. In Victorian England, many "penny dreadfuls" were written in the macabre Gothic tradition to frighten and thrill readers. The entrance of Great Britain and the United States into World War I provided a whole new field of material from which publishers could draw for the novels.

Dime novels typically told the dramatic adventure stories of a single hero or heroine who often found himself or herself in the midst of a moral dilemma. The novels were ethically sound, endorsing good character and strong moral values when the novel's hero chose virtue over vice. Sometimes, the protagonist was a historical figure, sparking the young readers' interest in history.

Women's dime novels typically dealt with romance and marriage, drawing on the social experience of the readers. Stories often set up a love between a working class girl and a noble and sometimes told of marriages and betrothals gone awry. Usually, these romantic ventures would end in disaster, warning the working class women that the emerging concept of an acceptable female sexuality was in fact, unacceptable. In these stories, virtue was protected at all cost, its importance emphasised for the sake of the readers.

The dime novel craze

Several factors contributed to the explosion in dime novel production during the last half of the nineteenth century.

First, updated technology allowed for the mass production and consumption of the works. The mechanization of printing and developments of new, cheaper types of paper allowed publishers to print more books in less time. These books were able to be distributed at a greater rate and to a further extent than before because of updated shipping methods. This updated transportation directly affected the reading public as well. As more people used public transportation with railroad and streetcars for commuting, they had more latent time to spend with short, light reading.

In addition to this, America was experiencing a significant rise in literacy rates. Coming off a decade of social reform, including a reform of schools and the enactment and enforcement of compulsory education law, the working class was more literate than ever before. A shift in the home from use of candles to oil lamps made it easier for readers to continue reading late into the night.

Additionally, public interest in the subject matter of the dime novels was high. With the battles with the Indians and the events of the Civil War, readers were looking for high action stories of the West.

Publishers

There were a few publishers who decided to cash in on the high business of the dime novels. Irwin and Erasmus Beadle and Robert Adams published the first dime novel under their publishing house, Beadle and Adams, in 1860. It was a short novel entitled Malaeska, the Indian Wife of the White Hunter, written by Mrs. Ann S. Stephens. Between 1860 and 1865 alone, Beadle and Adams published more than five million dime novels. During this time, the Civil War made soldiers a prime audience for the publishers who produced books that catered to the men needing mental stimulation during the boredom that often came with camp life.

A falling out between the brothers of Beadle and Adams led Irwin to pull out of the partnership. He joined up with George Munro, a bookkeeper in the publishing house, and they founded their own house, Munro. Munro began to publish its own version of dime novels, calling them "Ten Cent Novels."

Another major publishing house for dime novels was Street and Smith. This company viewed fiction as a commodity, and editors had strict authority over the authors' works. Each author was allowed limited room for immense creativity and was required to follow specific formulae in the plot lines and styles of writing they used. A surprising number of authors were willing to do so. Authors like Horatio Alger, Upton Sinclair, and Jack London wrote for Street and Smith under pen names to make the money that would come with their published works.

Authors

Not all of the authors were writing under pen names to save their reputations. Many were simply semi-professional writers who were often journalists, teachers, or clerks simply looking to make a bit more money than they could with their current occupations. Sometimes, authors wrote under pen names in addition to their real names in an attempt to increase their financial intake.

Some of the most well-known dime novel writers were Thomas C. Harbaugh, Albert W. Aiken, Edward L. Wheeler, Joseph W. Badger, Jr., and Colonel Prentiss Ingraham. Ingraham was the most successful writer of the short novels as the creator of the famous character, Buffalo Bill. He completed more than 600 novels in his lifetime, in addition to a number of published plays and poems. He was a master of his craft, pulling from his own military and travel experiences to create the scenarios in his stories. It is said that one his dime novel stories was written on rush order, the completed work containing 40,000 words on only 24 hours' notice, without a typewriter. With the invention of the typewriter, authors were able to churn out stories at an unbelievable rate. Frederic Marmaduke Van Rensselaer Dey, the creator of street-savvy detective Nick Carter, was rumoured to put out 25,000 words every week for almost twenty years, using multiple pen names. The high demand for the novels meant the authors made $200-$300 for each successful submission.

This financial draw incited many respectable authors to contribute to the genre. Famous names like Louisa May Alcott, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, Robert Louis Stevenson, and Alfred Lord Tennyson left their mark on the deluge of cheap fiction pouring from the publishing houses.

Women writers gained surprising recognition during this time. When Herman Melville and Nathaniel Hawthorne were selling several thousand copies of their works a year, author Fanny Fern sold 70,000 copies of her book Fern Leaves and 50,000 copies of Ruth Hall. Uncle Tom's Cabin, by Harriet Beecher Stowe, sold hundreds of thousands of copies. In 1872, seventy-five percent of books published were written by women.

Audience

The sale of dime novels was most highly concentrated in the industrial cities and mill towns of the North and West, where the largest groups of lower class people lived and worked in America. They were widely read by the lower classes, primarily by boys and young men, though some girls, grown men, and some groups in the middle class enjoyed the books, as well. Many people, especially of the middle class, were ashamed to admit they read the novels, as they were not necessarily quality reading material and were only mindless entertainment with which to while away the time.

While it is not as well-remembered today, there was an audience of women for dime novels, too. Many young, working and middle class girls and women enjoyed the stories of romances in the pioneer realm, sensational murder mysteries, and society romances. Bertha M. Clay, Geraldine Fleming, and Laura Jean Libbey were the more prominent female writers of novels like All for Love of a Fair Face, The Story of a Wedding Ring, A Charity Girl, The Unseen Bridegroom, and Only a Mechanic's Daughter.

The lasting influence of the dime novel

It would be hard to say that the nature of the dime novels has been lost. While the 1890s brought the entrance of pulp fiction magazines into the publishing arena, they were heavily influenced by the dime novels. Rising post rates may have caused a decline in the publication of the dime novel, but the content and sentiment behind the works continue to influence publications even to modern day. Sensationalist celebrity gossip magazines, romance paperbacks and romantic comedies, horror movies and ghost stories, and exaggerated tall tales are all directly or indirectly the result of the dime novel craze.

Further reading

The HA is not responsible for the content of external websites

- Street & Smith Dime novel covers (Syracuse University Libraries)

- Dime Novels and Penny Dreadfuls (Stanford University Library)

- Dime Novels Timeline (Stanford University Library)

- The American Women's Dime Novel Project

- A short history of the paperback (IOBA Standard)