Teaching History 166: Out now

Journal

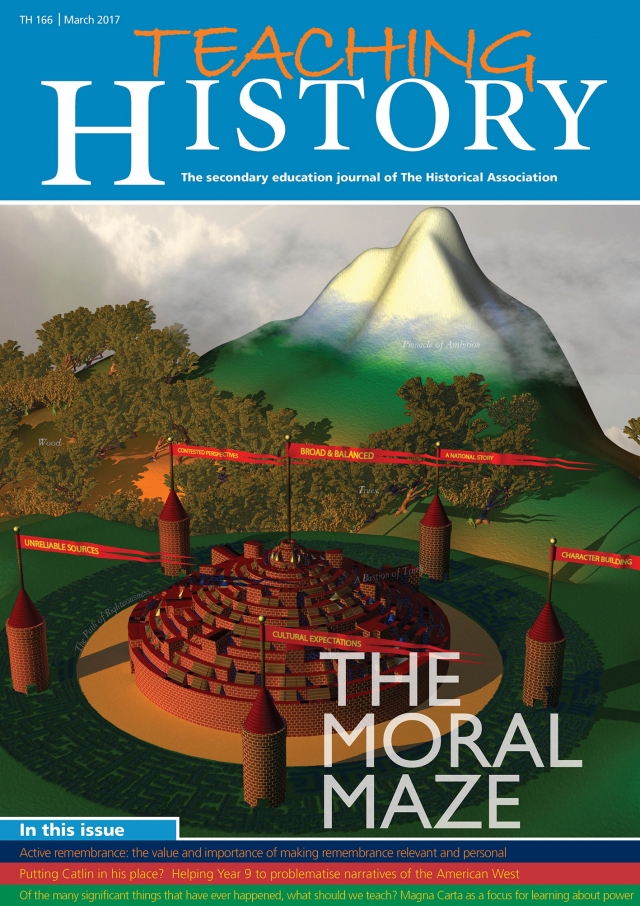

The Moral Maze

What are we trying to achieve through teaching history? What are we trying to achieve by teaching at all? As readers of this journal we practise our craft in a variety of educational settings and geographical locations – are all of our aims and purposes the same? Should they be? This edition is essentially concerned with this question of how things ‘should be’ – that is with questions of entitlement and of morality – looking in particular at issues of curriculum design and delivery and of teacher choice, as well as the ways in which our students’ and our societies’ reactions to the past can and should be shaped and moulded.

The guidance that teachers in England and Wales are given is clear. Educators should make certain that they remain politically neutral. They must also ensure that Fundamental British Values (FBVs) are nurtured among their students.1 These values – mutual respect and tolerance, democracy, liberty and the rule of law – must be accepted. This is, of course, not politically neutral. Our system is designed to produce liberal democrats (both words are firmly in lower case). Thinking about the discipline of history itself, what should we do as historians when we study the history of individuals or cultures whose behaviour was clearly (to modern, FBV-tinted eyes) amoral or immoral? We cannot become completely relativist: as modern citizens we must criticise the Nazis. But should we criticise them in our role as historians? Or avoid the question? Should we criticise Thomas Jefferson, the author of the Declaration of Independence, that key document asserting the fundamental equality and inherent liberty of all men, who also owned hundreds of slaves? That question was posed to us as historians – what about us as teachers, whose charges are developing as historians, but also as citizens, moral actors and critical thinkers? Is it our place as historians to praise or condemn?

Jess Landy engages in her article with George Catlin, whom she describes as enlightened for realising that Native Americans were more than just savages – they were people. This was heady stuff for nineteenth-century American cultural figures. Catlin’s attitudes were in fact more complex than that – he was only, it seems, partially convinced – but Landy recalls, as an eight-year-old, finding the idea that anyone might not have accepted the humanity of Native Americans baffling. Landy discusses the sense of otherness modern students have when dealing with people in the past whose ideas seem to them to have been immoral, and provides some suggestions for dealing with this through the creation of mini-narratives. Landy’s article might profitably be read in the context of the guidance that this edition provides for those new to, novice in or nervous about teaching about controversial issues. The NNN feature considers narrative construction and choice as well as politics and curriculum design. Rachel Foster’s Cunning Plan for teaching about the Crusades also helps usstto think about enabling students to analyse the motivations and actions of those whose worldview appears, in her words, ‘utterly alien and yet unnervingly human.’

Many schools, both in England and Wales and around the world, recognise Armistice Day, 11 November. A fair few hold their own annual Remembrance event. All schools have been encouraged to visit the battlefields, usually in Ypres and on the Somme, where many British lives were lost in the First World War. Claire McKay describes how she has worked with the Centenary Battlefield Tours Programme to plan such a trip, showing how it fits in not just to the history curriculum but also to all the citizenship and spiritual, moral, social and cultural (SMSC) work of her school. Remembrance is a cultural issue, but also a political one. Our (British) society chooses to remember the sacrifice of ordinary soldiers in the First World War, with tremendous pomp and solemnity. How does this integrate with our attempts as history teachers to encourage our students to think critically about the causes of the First World War, about the reasons why people joined up, about just-war theory and about how that particular conflict should be construed in moral terms? Bjorn Wansink, Itzél Zuiker, Theo Wubbels, Maurits Kamman and Sanne Akkerman consider varying perspectives on another conflict – the Cold War. By engaging with students in countries in the former East and countries in the former West, and bringing those students together, they also engage with families with cultural memories of the Cold War. Their article, which might be read in conjunction with Aaron Watts’s contribution to Polychronicon, examines a sensitive issue, and provides a framework for transnational co-operation at a point where the history we choose to teach is highly politicised.

Michael Fordham and Tony McConnell, in separate articles, examine issues underlying curriculum design. Each is seeking moments at which students might be asked to remember material they have previously studied. Fordham is seeking to start a debate about the role of cognitive psychology in lesson and curriculum planning; McConnell is looking for the role of the story of democracy, as told through Magna Carta, in providing a framework for an entire programme of study which works in the context of his school.

We hope that you find useful activities which you can take from this journal, and that you are inspired to design other activities which are similar (and better). We hope that you agree with some of what the authors argue. But we hope you disagree, too. Please share your ideas with us – perhaps in the form of contributions to future editions. In the meantime, we hope that we have provided some guidance for those engaged on a journey through history teaching’s moral maze.

REFERENCES 1 Ofsted School Inspection Handbook, last updated August 2016, www.gov.uk/government/publications/schoolinspection-handbook-from-september-2015, p.35