The Historian 134: out now

Journal news

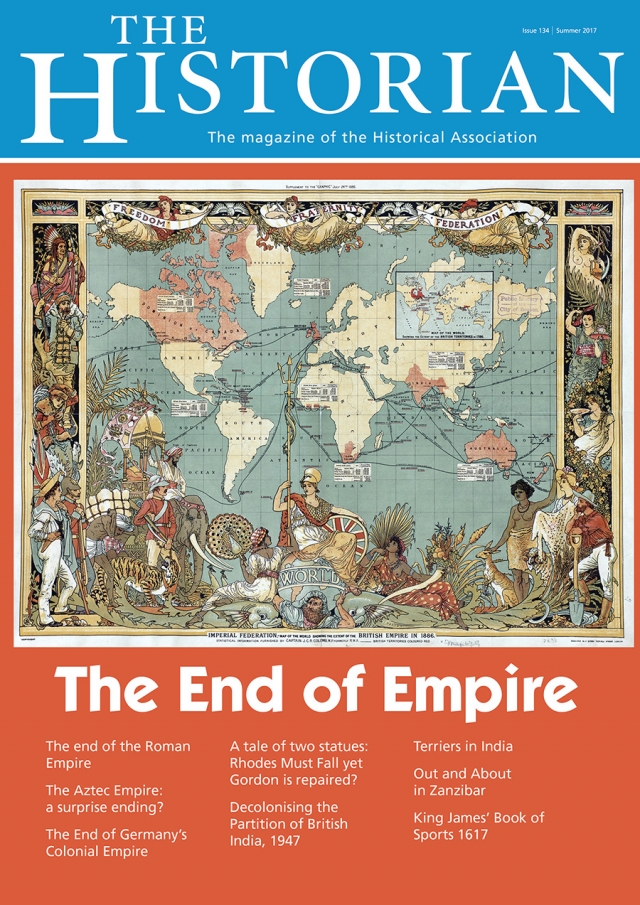

The End of Empire

The idea behind this edition emerged from a discussion on how we ought to commemorate the 70th Anniversary of Indian independence. From that, our discussions widened to consider how empires end in general, and to discover where new thinking about this can help us understand the dynamics of Empire.

Most families in Britain will, we think, have an ‘Empire’ story. My own family certainly does. Dad had never been away from home before he was called up for his National Service in 1947 and found himself serving in the Dental Corps in the Canal Zone, Egypt. Uncle Jim, having served with the ‘Chindits’ during the Second World War became a colonial administrator in Singapore from 1947 until Independence. He was well rewarded for his endeavours – good wages, luxury accommodation, cook, servants and gardener, long periods of leave and excellent schooling for his children. My own son has taught in both Mauritius and Malawi, and both my sisters live in Canada. Distant relatives emigrated to Australia late in the nineteenth century and seem to have prospered, owning a canning factory and a very successful business – family legend has it that in the hard times of the 1920s and 1930s every time a ship from Australia docked in Sunderland there was always a case or two of canned stewed beef from the rich relatives in Australia! Professor Peter Stanley of the University of New South Wales, Canberra, seeks to tap into these Empire stories. He is researching the stories of those 50,000 British Territorial soldiers who served in India during the First World War, and his appeal asks for your help. Here is a chance for you to play your part in an ongoing academic research project. If you have memories of family members please do get in touch with him.

Guy de la Bédoyère examines the end of the Roman Empire, suggesting rather than coming to a sudden end, as many historians imply, it simply transformed itself and evolved through change to help make the world we live in today. Matthew Restall similarly questions our current beliefs about the end of the Aztec Empire in Central America, suggesting that much of what we think happened is based far too closely on the writings of the Conquistadors. Amrita Shodan revisits the events in India of 1946 and 1947 and suggests that local actions might be as important as national actions in the way Partition happened. Daniel Steinbach, in the latest in our ‘Aspects of War’ articles, looks at the German colonies in Africa and sees ‘End of Empire’ through transfer from one empire to another following military defeat. Finally, Dave Martin explores the contrasting fates of two statues – that of General Gordon in Khartoum and Cecil Rhodes in the grounds of the University of Cape Town, and asks what their contrasting fates tell us about Britain’s attitude to Empire. This perhaps helps to shed some light on the recent failed campaign (2015-2016) in Oxford to remove Rhodes’s statue from Oriel College. How should we in Britain remember the Empire, and our imperial heroes?

Our regular features too feature an Empire theme. ‘Out and About’ explores Zanzibar, famous for cloves and the lucky recipient of three imperial regimes – Arab, German and British, as well as the home of the ‘Shortest War in History’ (see The Historian 123, November 2014), and, for a time, Freddie Mercury! ‘My Favourite Place’ explores Hadrian’s Wall – literally the edge of Empire.

I vividly remember standing on Whin Sill Crag, in a howling gale, with 40 15-year-old students while a colleague read ‘Roman Wall Blues’, by W.H. Auden. The first four lines read:

Over the heather the wet wind blows, I’ve lice in my tunic and a cold in my nose.

The rain comes pattering out of the sky, I’m a Wall soldier, I don’t know why.

That, as much as anything, seems to help explain the end of Empire!

Alf Wilkinson

In his acceptance speech for last year’s Medlicott Medal Sir Antony Beevor argued strongly that he saw his work as literature and was somewhat critical of Scandinavian scholars who believe that historical research is a form of scientific enquiry. Your editor is inclined to this latter view because what we eventually write and offer to a wider public is based on methodical and clinical exploration of sources, comparison with parallels and finally analysis at the end of the process. A sixth-former, writing in the current Stonyhurst College PAST magazine, has crystallised this idea for me in writing about the Defenestration of Prague in 1618. We all know that the two representatives of the Holy Roman Emperor were thrown out of the window of the Royal Palace and that, broadly speaking, this marks the beginning of the Thirty Years War in Europe. The detail of the event is agreed but the circumstances are open to much speculation and research. Some Catholics believe that the two men were saved effectively by divine intervention but, more prosaically, we do now know that a strategically-positioned wagon was in place under the window – some say containing straw, others say manure – to catch the two victims. So this means that this defiant act was an act of intended humiliation rather than a serious physical threat, and further research reveals that, indeed, this was a fairly regular way of demonstrating displeasure with the authorities. This instance, in a sense, proves that Sir Antony and I may both be correct: this will always be a good story well told but it also has a backcloth of clinical enquiry.

We are extremely grateful to Alf Wilkinson and his team for providing us with a series of insights into the broad theme of ‘Empire’. What they have provided for us serves to remind us that our themed editions do take a very broad sweep in exploring a chosen theme.

Trevor James