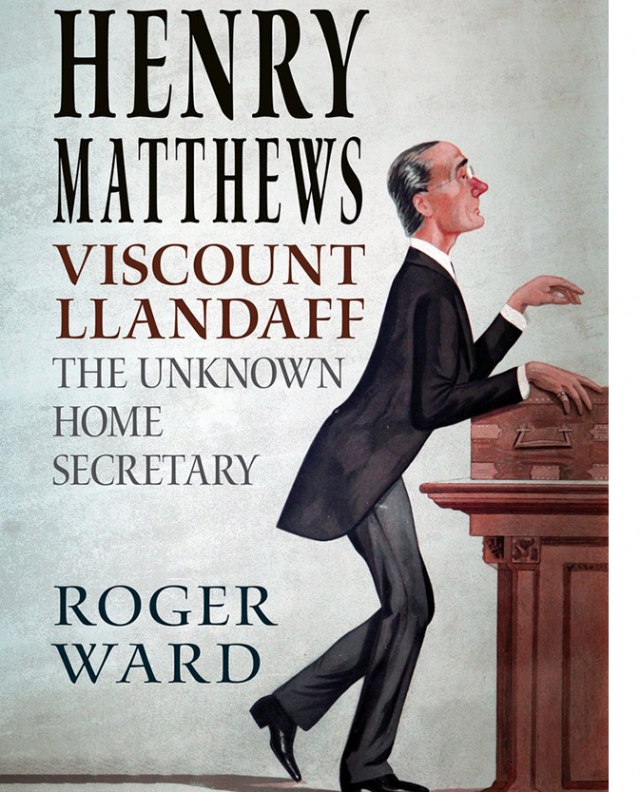

Henry Matthews, Viscount Llandaff: The Unknown Home Secretary

Book review

Henry Matthews, Viscount Llandaff, The Unknown Home Secretary, Roger Ward, Fonthill Media, 2019, 96p, £16-99. ISBN 9781781557150.

Despite Henry Matthews’ attempt to obstruct a biographical record of his life being prepared, by instructing his niece to burn all his private papers, Roger Ward offers us a well-composed and well-balanced assessment of his political and private life.

Having served as the MP for the Irish constituency of Dungarvan between 1868 and 1874, he had a reputation amongst Conservatives of being a liberal on social issues. This brought him into contact with Lord Randolph Churchill who was trying to promote progressive Conservatism with his Tory Democracy stance. As a result, with Churchill’s support, in 1885 he stood unsuccessfully for the North Birmingham seat but was elected for East Birmingham in the General Election of 1886. In securing this seat, he was the first Conservative to represent Birmingham in Parliament since 1847. Having previously been considered by Disraeli as a possible Solicitor-General in 1874, prior to losing his seat, in 1886 he was propelled with Churchill’s support into the senior Cabinet post of Home Secretary, becoming the first Roman Catholic since the early 18th century to serve as a Cabinet Minister.

Roger Ward, to paraphrase, places to the remarkable Henry Matthews as the right man in the wrong job, or possibly vice versa. With the personal support of Churchill almost immediately removed from the Government, his brand of liberal Conservatism did not really fit the mood of Salisbury’s Government, and the challenges which beset the Home Department, as is always the case, prevented him from making his particular mark. Thus his talents were under-used and he left office in 1892 when Salisbury lost the General Election.

Roger Ward gives a roundness to this figure, professionally, politically and personally, and we are left wondering what this mildly progressive man could have achieved in Disraeli’s reforming Government of 1874-80 or in partnership with Lord Randolph Churchill. As it is we are presented very effectively with Matthews in the midst of the political struggles of the late 19th century by the writer who is pre-eminently the expert on later 19th-century Birmingham politics.