Teaching History 188: Out now

The HA's journal for secondary history teachers

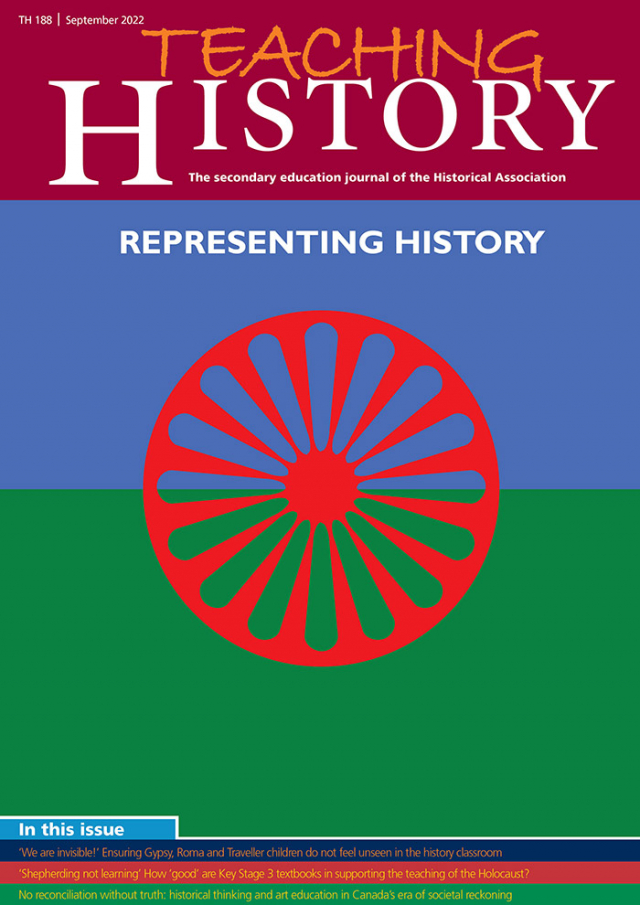

Editorial: Representing History

Read Teaching History 188: Representing History

History teachers are familiar with the challenges that arise as we try to help our students make historical sense of past worlds. Building historical representations of the past is imaginatively demanding – it requires ‘world-making’ and narrative expertise. The challenges are probative, not merely narrative, since understanding histories involves grasping them conceptually, as warranted arguments, and not just imaginatively, as compelling stories.1 There is more to understanding history than understanding sources, concepts and narrative discourses, however: representing history is bound up with power in the present.2

Links between power and representing history can be seen in archives, where decisions about what is ‘worth’ keeping and curating are enacted and where the act of ‘collecting’ presupposes control of economic and other resources. Historical interpretations express judgements and the power to make them: decisions about what to focus on and about whose and which stories to tell. Wider social distributions of power shape which traditions of history-making and which people and communities are empowered to ‘tell’ histories. Decisions about narrative practice shape agency in histories, which agents, actions and contexts are depicted, and how they are ‘shown.’

The articles in this edition explore the decisions about representation that our curricula, resources and practices embody. They all aim to help history teachers reflect on representation and, perhaps, represent history differently.

Richard Kerridge and Helen Snelson address the invisibility of Gypsy, Roma and Traveller (GRT) history in schools. They draw attention to existing materials on GRT stories and histories and share resources they have created to enable GRT history to be integrated into the curriculum in meaningful ways. These materials enable personalised GRT histories to be explored through micro-narratives – enquiry focused on Mary Squires dramatising social change in the mid-eighteenth century and on Jack Cunningham VC illuminating aspects of the First World War through one GRT story.

Textbooks represent history as an activity and way of knowing the world, and through the accounts which they contain. Convinced of the value of good textbooks, Alex Diamond set out to understand teachers’ thinking about how textbooks could represent Holocaust history adequately. As Diamond’s discussion shows, this is a multi-faceted issue. Evaluating textbook representation involves reflecting on aims as much as content and it requires history educators to be clear about their aims. It also involves, for example, thinking about the ethics of representation, and about how we represent the people and events of the past in our classrooms.

Two teachers, Nathaniel Davies and Taslima Rakib, and an oral historian, Anam Zakaria, report their collaboration to integrate difficult Bangladeshi histories into the curriculum. Davies developed an enquiry working with Zakaria’s oral history of the period, aiming to help pupils in a majority Bangladeshi-origin school feel present in the curriculum and to challenge Eurocentric visions of school history. He explores why some stories of this period have been harder to tell than others and how power and powerlessness can shape history-making. Finally, Davies reports his struggle to develop the most suitable enquiry question and Davies and Rakib reflect on their own and their pupils’ experiences of learning.

Michael Pitblado and Agnieszka Chala address historic injustice through an arts-integrated history project, that brings together the disciplines of history and art to help students encounter the history of Canadian Residential Schools and to represent and exhibit their reactions to this history. Drawing on the conventions of Banksy's graffiti works, their students started down a path towards conveying a more nuanced understanding of Canada’s treatment of indigenous peoples.

Sam Ineson wanted his students to understand the Holocaust in its historical complexity and to combat misconceptions seeded by contemporary Holocaust memory and popular culture. Over a three-year period, Ineson set out to integrate the historical Holocaust into his school’s curriculum, developing a scheme of learning that embedded the stories of the Holocaust into the wider narrative of the Second World War and that explored events at the individual level, challenging stereotypes. Ineson also created a school museum, bringing Holocaust artefacts into pastoral and history teaching, and integrated a Holocaust timeline into the fabric of the history corridor.

Concerned by her students’ stereotyped and anachronistic representations of the medieval past, Jessica Phillips decided to explore whether a deliberate attempt to shift their perspectives on this history could help change how they represented the medieval past. Phillips used Shemilt’s categories ‘psyche-snatcher’, ‘time-traveller’ and ‘necromancer’ to distinguish different types of empathetic sense-making.3 Phillips then developed a scaffolded response grid to help students read past practices in terms of differing senses of the ‘normal’ and the ‘strange’, drawing on a systematic exploration of different senses in which ‘presentism’ could be used to make sense of the past. Positive changes were seen in the representations that students developed.

References

1 Hill, M. (2020) ‘Curating the imagined past: world building in the history curriculum’ in Teaching History, 180, How History Works Edition, pp. 10–20; Megill, A. (2007) Historical Knowledge / Historical Error: a contemporary guide to practice, Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

2 Trouillot, M. (2015) Silencing the Past: power and the production of history, Boston, MA: Beacon Press.

3 Shemilt, D. (1984) ‘Beauty and the philosopher: empathy in history and classroom’ in Dickinson, A.K., Lee, P.J. and Rogers, P.J. (eds.) Learning History, London: Heinemann, pp. 39–84.