Teaching History 191: Out now

The HA's journal for secondary history teachers

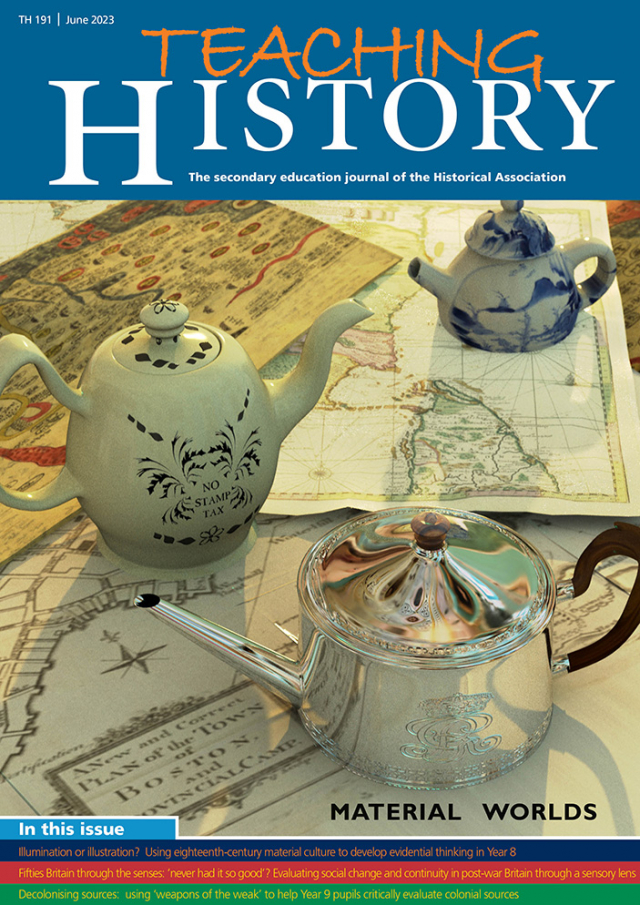

Editorial: Material Worlds

Please note: the print edition of Teaching History 191 will arrive with members in mid-July.

Has the materiality of the past been neglected in secondary school history? Many history teachers might be surprised at the question. After all, enquiries featuring social, economic and cultural realities have long been explored and discussed in this journal. Historians of material culture, however, offer refreshingly distinctive methods for interrogating sources, and, as Eleanor Dimond argues in this edition, if we teach these to our students, we open up new ways in which objects can illuminate the past.

The study of objects was once associated with antiquarianism rather than history, but this is a far cry from a material culture approach. Asking her pupils, ‘What can a teapot tell us about eighteenth-century society?’, Dimond taught them to shape an object’s biography – the story of its creation, use, transfer and disposal. By examining the people who made and used the teapot, as well as its social functions, its physical settings, and what the object itself can reveal about all this, an object can become a gateway to a social world. Gabriella West adopted a similar approach to the life cycle of a silver casket from Mysore. Having specialised in the history of material culture during her degree, and being inspired by the work of historians such as Sarah Longair, Gabriella West was troubled by the dismissive attitude of her pupils towards the study of material objects. She therefore set out to find the perfect object through which to induct her Year 8 into the value of material culture to an historian. West’s resulting enquiry illuminated the history of both the Mughal and the British empires in India, and, at the same time, some silences in existing interpretations. Longair herself joins the edition with a concluding reflection on the significance of West’s work.

An approach which builds a strong interplay between analysis of the physical attributes of an object and analysis of its context stands in stark contrast to typical examination questions relating to sources. It is a sad irony, therefore, but likely to be no surprise to history teachers, that the only way Bartington felt able to tackle significant weaknesses in her students’ evidential thinking was to move right away from the conventional questions on a source-based paper. She chose to use, instead, a collection of sources related to her students’ work on the historic site of Kenilworth Castle. Indeed Bartington noticed that her students’ focus on examination questions about sources appeared to have undermined their understanding of how historians actually use sources! Instead of approaching the traces or ‘leftovers’ of the past as potential sources of evidence in relation to a particular question, her students believed that they could rate their usefulness or reliability as fixed properties. Inspired by other history teachers’ use of source collections to solve similar problems, Bartington used a collection of sources related to Kenilworth Castle to teach her students that we can use the same source to generate different kinds of evidence in response to different questions.

Stiasny similarly pushed the boundaries of examination requirements. She chose to illuminate facets of the 1950s that her new A-level students appeared not to grasp, namely how the period looked, felt, smelt, tasted and sounded. Only thus, reasoned Stiasny, could her students hope to be engaged with, let alone make informed judgements on, the question of whether that post-war generation ‘had never had it so good’. Stiasny taught her students to use a sensory lens to build a picture of their period. She created an anthology of sources through which they might build a rich picture of the sights, sounds, tastes, smells and textures of post-war Britain.

Danielle Donaldson also writes about new strategies for close reading of sources, but her department’s work arose from a process of asking fresh questions about what it really means to decolonise a curriculum. Donaldson wanted to equip pupils with a more active and critical way of challenging dominant narratives. Drawing on the work of Priya Atwal and other historians, Donaldson and colleagues eventually settled on a new enquiry about the Sikh ruler, Maharani Jind Kaur. For the close reading of sources, Donaldson considered various options, but eventually drew on a way of studying everyday forms of resistance – ‘weapons of the weak’ – developed by anthropologist James C. Scott.

The theme of reading sources for resistance is picked up by Nathanael Davies and Harry German, in this edition’s Cunning Plan. Creating their own ‘history-from-below’ archives, students learned to read both written sources and artefacts for inferences about resistance to transatlantic slavery. In this way, they learned ways of filling gaps and silences in long-standing interpretations of the period.

Ian Luff ’s return to Teaching History might, at first glance, appear to be the exception in an edition focusing almost entirely on re-reading the traces left by the past, but Luff develops the theme of this edition by showing ways in which the past can become concrete for pupils. Each of his ‘practical demonstration’ activities opens up a key aspect of the material world – from machine gun fire to Lister’s antiseptic spray to the geographical facts of mutually assured destruction (MAD). Using current discussions of research into the cognitive science of memory, Luff gives his fullest rationale yet for his popular ‘practical demonstrations’ showing their power to capture imagination, make lasting memories, prompt deeper and more rigorous historical thinking, and all while saving history teachers a great deal of time.

This is an edition of profound curricular innovation, right across the board. Each author has sought a way to solve a problem to plug a gap in students’ historical understanding. Each has found a solution by opening up a fresh role or a fresh method for analysing material worlds.