Teaching History 183: Out now

The HA's journal for secondary history teachers

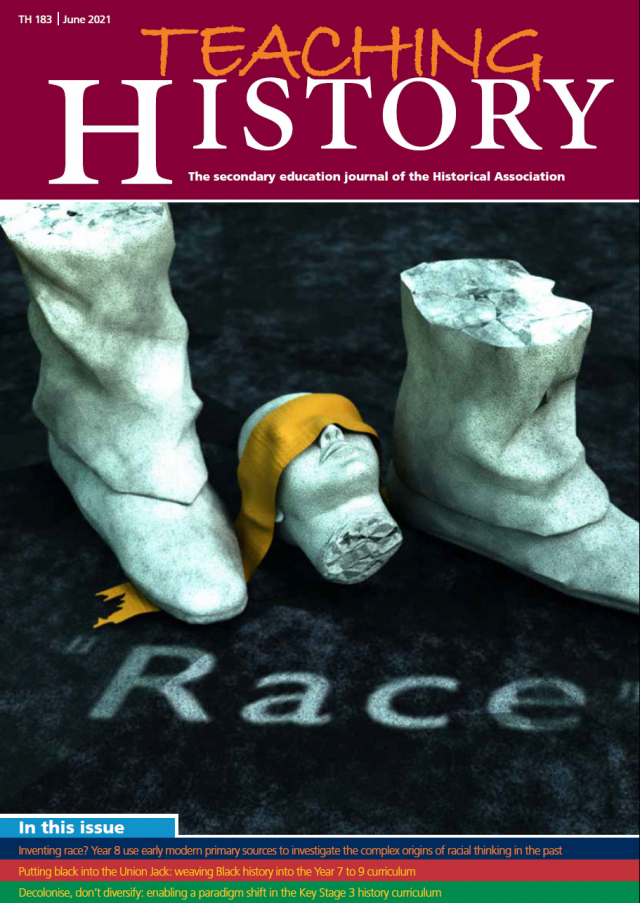

Editorial: Race

Read Teaching History 183: Race

Collectively, the articles in this edition say something profound about the joy and privilege of being a history teacher. In our intellectual journeying, none of us can ever stand still. Conversations within and across societies and cultures never stop. Such conversations interact with the work of historians through the questions they ask, the methods they pursue, the new truths they seek, the accounts they produce and the way in which they sustain or renew the very standards to which they hold themselves to account. The curricular work of history teachers must interact with all of these. History teachers constantly make choices about which content to teach, how to arrange and blend it and how to frame questions through which to teach historical method. Over the past eighteen months in particular, the topic of race has newly challenged history teachers’ historical imagination, scope of analysis, breadth of knowledge and ethical responsibilities. History teachers everywhere have been responding both to broader cultural conversations and to new works of historical scholarship. As we shape our curricular journeys, we find ourselves asking, with respect to race, what are we revealing? What are we concealing? How can we notice where we have inadvertently ascribed significance or silence?

These questions show how intricately interwoven all aspects of the intellectual work of history teachers are. In the What’s the Wisdom On of Teaching History 181, as we editors sought to summarise history teachers’ work on historical significance, we found ourselves showing its relationship with new work on historical silence. Thus the way we frame the disciplinary dimension and relate it to the substantive is ever changing too.

Kerry Apps begins this edition by sharing how she linked substantive knowledge and disciplinary thinking in her teaching about the origins of racial thinking. Her account moves steadily and intriguingly through the journey of a workscheme in which Apps slowly peeled back layers of source material. Bit by bit, Apps’s pupils were enabled to make their own inferences as they discerned the ways in which changing attitudes to African origins began to affect the lives of indentured labourers.

Hannah Cusworth then shares a very personal journey. She charts her own experience as a mixed-race pupil, as a student of history and as a teacher who belatedly realised that there were many more stories with which she and others could identify, but which she had not heard. Cusworth’s piece is fired by passion for broadening all pupils’ interests, curiosities and assumptions, but the seam running through it is the intensely powerful effect of history on a pupil’s sense of identity. Cusworth writes about feeling ‘out of place’ as a teenager. Sharing her later discovery about Aina Forbes Bonetta, the Yoruba princess, she writes:

One thing that did not separate us was distance. In fact, where Aina lived in Brighton is four minutes’ walk from where I went to secondary school. I was 30 when I found that out. I cried. Knowing of her presence made me feel different. It made me think differently about where I grew up. It turned out that being Black in Brighton was not as new as I had thought. I wonder how differently I would have felt if I had known that as a teenager.

In Liam Liburd’s Polychronicon [What Historians Have Been Arguing About...] we gain a useful overview of sometimes fierce debates among historians about the impact of the British Empire on Britain. Many historians have explored the ways in which modern Britain has been constituted by her global connections but their preoccupations, scope of concern, response to recent events and use of sources all differ. This has consequences for curricular choices that we might make concerning when and how to introduce such debates to pupils.

Josh Garry shares how he introduced one such debate, but this time a sixty-year-old one generated by the activist and historian Walter Rodney and his thesis concerning the ‘underdevelopment’ of Africa. Garry explains his planning journey, showing how his growing knowledge of the kingdom of Benin, wide reading of scholarship and discussion with other history teachers on an HA fellowship programme shaped his planning. Dan Lyndon-Cohen likewise shares a planning journey. Already proud of a richly diverse curriculum which he had written about in this journal, Lyndon-Cohen and his colleagues concluded that there was still something missing. They decided that that more radical change was necessary – the very lens through which they were viewing the past was a colonial one. Thus they moved further into content choices and journeys that were designed to change pupils’ ways of viewing the past, including a challenge to the discipline of history itself for marginalising indigenous voices.

Both Helen Snelson’s Cunning Plan and Theo Woods’s article continue the theme of communities of history teachers saying ‘Hold on, I think we can do better’. Working with Ruth Lingard, Helen Snelson designed new resources that would radically broaden seventeenth-century content into diverse lived experiences. Meanwhile, Woods and her department embarked on a substantial process of curriculum review and development addressing the full seven years of students’ secondary experience and pulling it away from its former reliance on ‘traditional, White and Eurocentric’ topics.

Finally, Afia Chaudhry considers the teaching of Islamic history from two perspectives, that of Muslim students themselves and that of students not of Muslim heritage who nonetheless hold a range of assumptions about modern Muslims. Drawing on varied research on the experience of Muslims in British schools, and her own small study of all her students’ perceptions, Chaudhry sustains the twin themes of the needs of Muslim and non-Muslim students, with an ultimately inspiring vision that is a fitting conclusion to this thought-provoking edition – how the histories we teach allow everyone to feel that they belong while also interesting everyone in one another’s heritages. Thus they make possible a new ‘sense of community among all pupils’.